My name is Elena Bird. I’m a junior (third year undergraduate student) at Dartmouth College, where I am studying Earth Science. I will be your tour guide (main blogger) during our upcoming trip to Antarctica, so here's a little introduction.

My dad studied geology in college and continues to love it, so I grew up inundated with facts about rock formations, mineral identifications, and mountain ranges. I was born in Andover, MA and split my time between there and the White Mountains of New Hampshire. My family spent a lot of time traveling in places like Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and Wyoming during my childhood. I loved seeing the sweeping stratigraphy of folded sandstone in the southwest and the jagged peaks of the Tetons in Wyoming. Between summers of backpacking trips and winters dedicated to skiing I developed a love for and fascination with the earth and its natural systems.

My appreciation manifested into concern, and I dove into environmentalism through school clubs, internships, and organizations. I was drawn to Earth Sciences because of my interest in climate systems and global climate change. Glaciers and Ice sheets have become particularly interesting to me in part because of their immense influence on climate and ocean circulation, but also I just think ice is super cool!

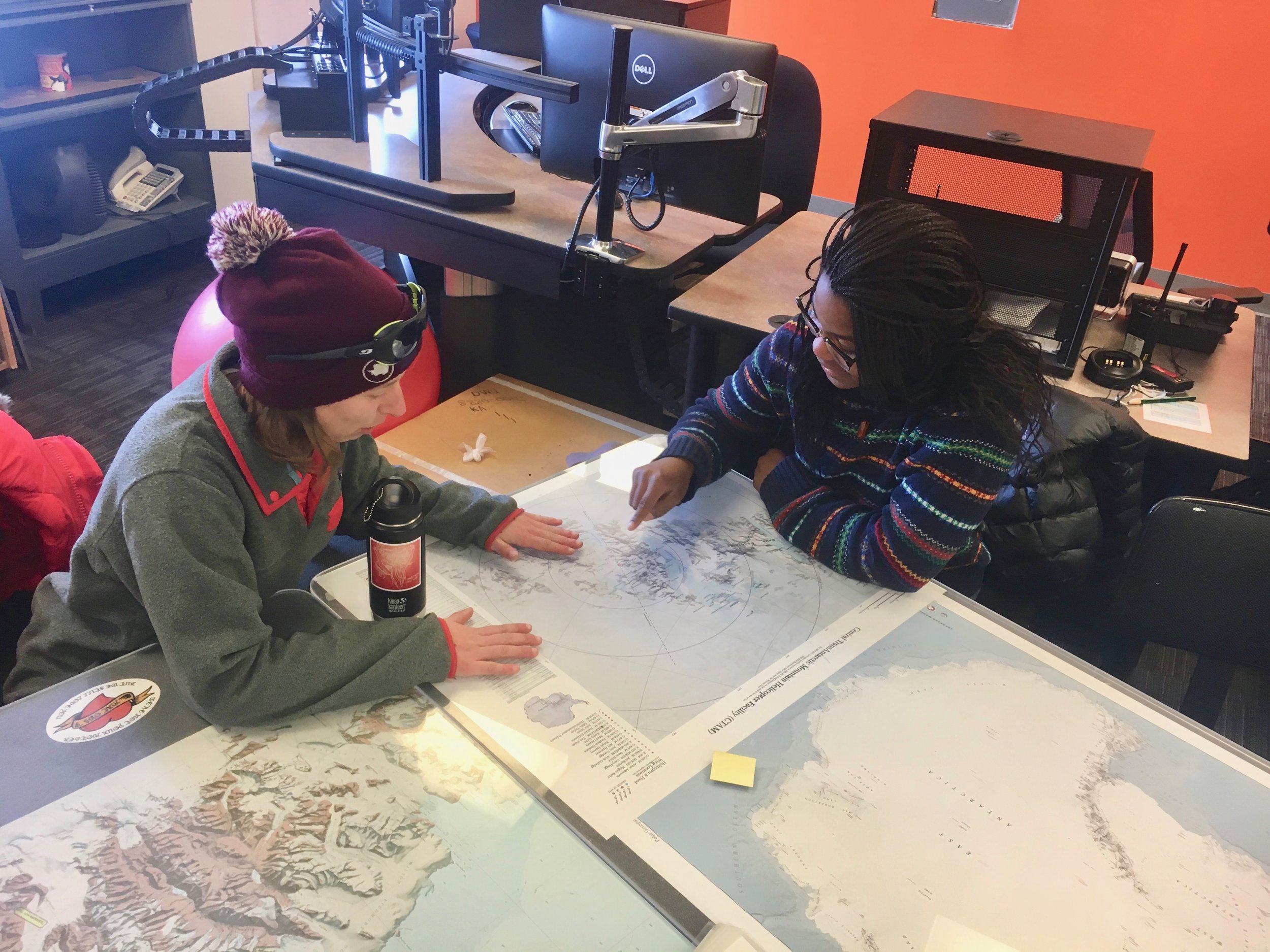

I began doing research for Professor Rachel Obbard, the Co-PI for the VeLveT Ice Project (The PI, or Principle Investigator, is Professor Erin Pettit, from the University of Alaska, Fairbanks) when I started at Dartmouth. Rachel is a specialist in ice microstructure, and I have been helping her create maps of the crystal orientation of ice samples. (More on that later too.) This is what’s brought me here -- joining the Velvet Ice team, writing this blog, and preparing for a big journey south!

The VeLveT Ice Project

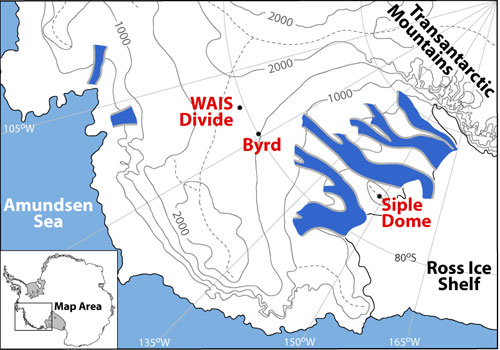

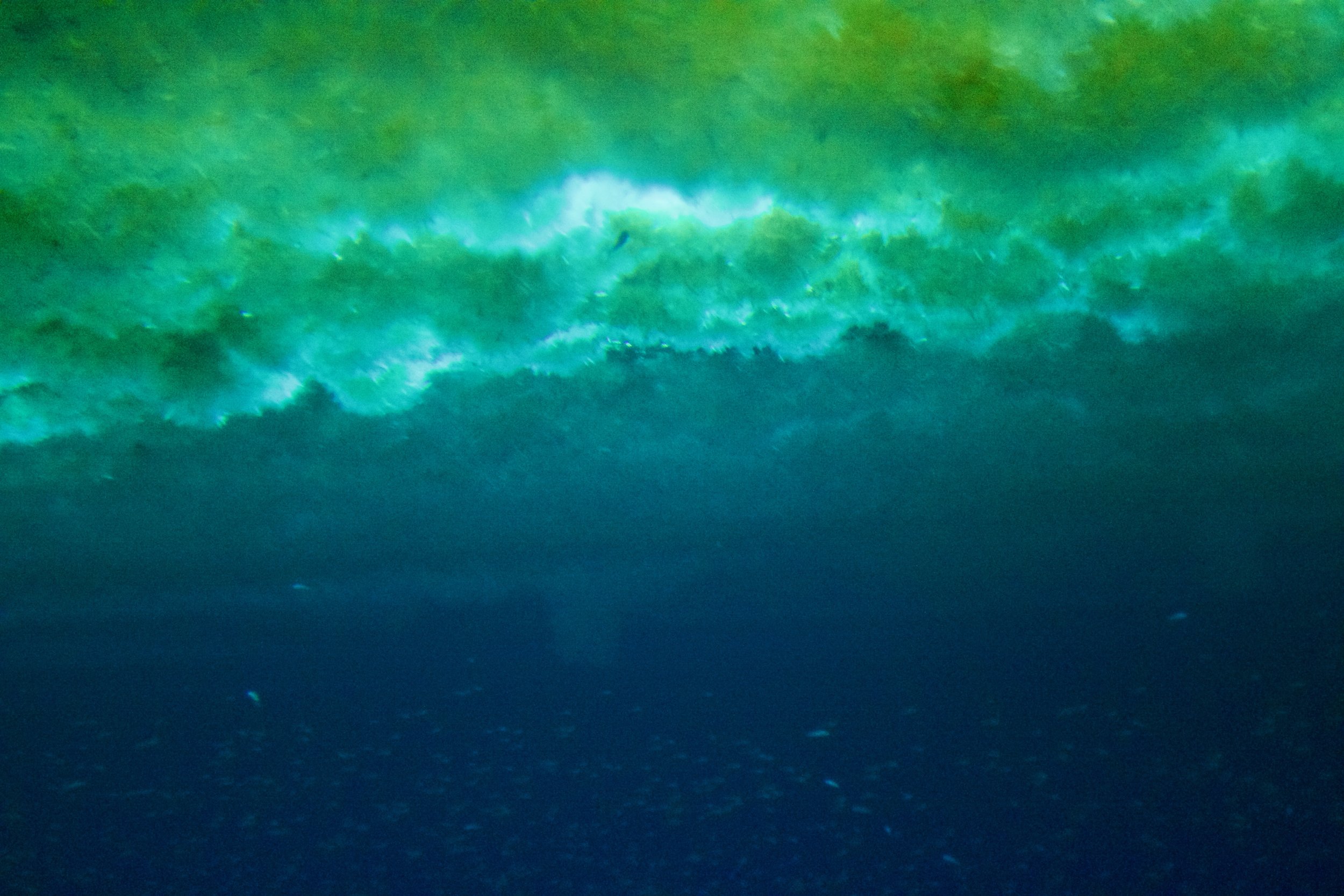

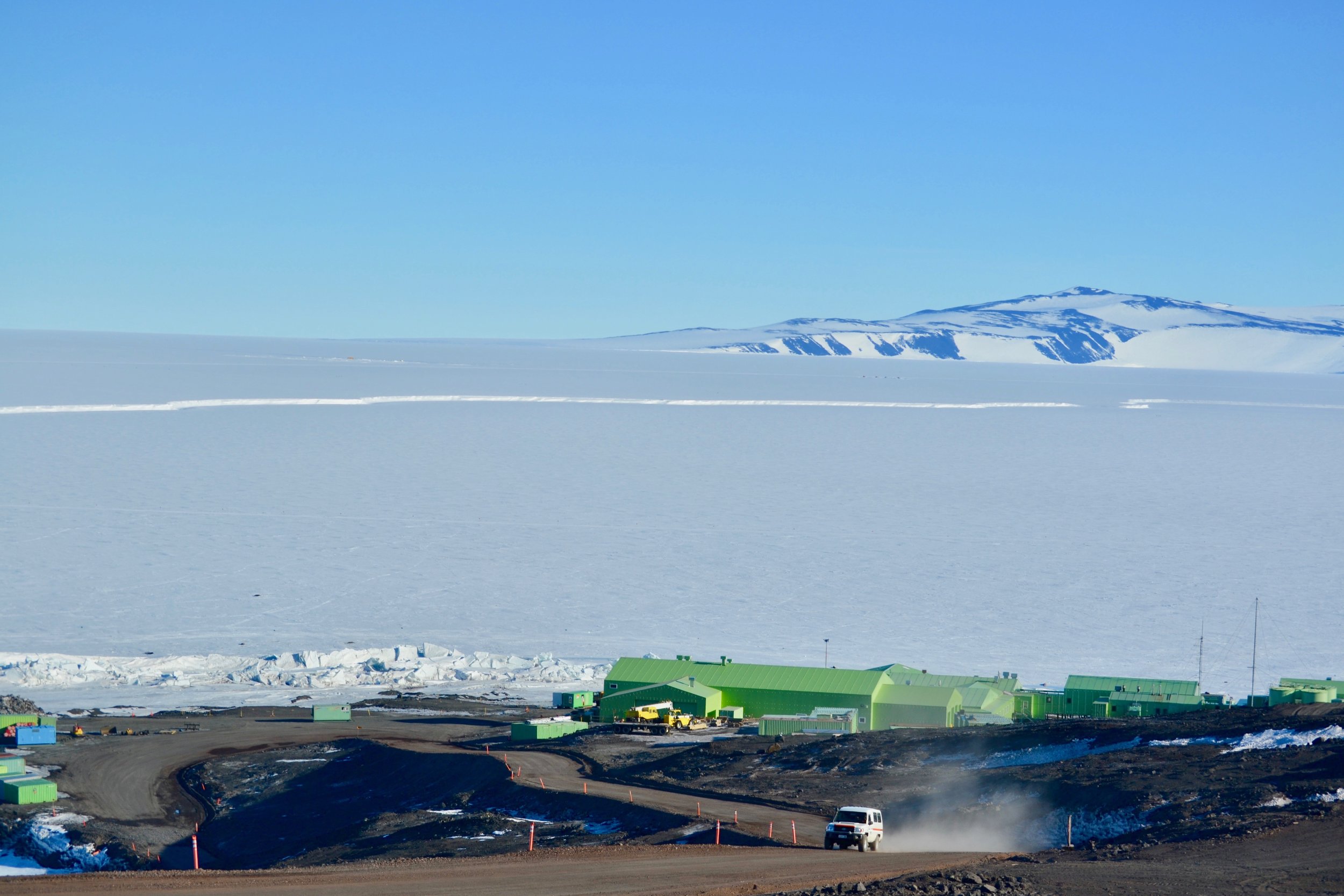

The title of our project is “Collaborative Research: VeLveT Ice - eVoLution of Fabric and Texture in Ice at WAIS Divide, West Antarctica,” and we are funded by the National Science Foundation, Division of Polar Programs. The Velvet Ice team is observing the ways in which ice crystal orientation affects the flow of ice sheets. Ice sheets contain records of Earth’s climate history. Scientists extract ice cores in order to study the layers that make up the ice sheet. The chemistry of the different layers reveals climate history, and the physical properties of the ice - crystal size, shape and orientation – tell us about the englacial environments (in which the layers formed), and both affect and are affected by the flow of the ice. By comparing variations in microstructure (crystal size, shape and orientation) to macrostructural deformation (flow of the ice sheet) we will gain a better understanding of the dynamics and history of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS). A better of understanding of this history will improve other scientists’ analysis of the climate records the ice sheet holds. The borehole that remains after the collection of an ice core provides a means to study the large scale flow and deformation of the ice.

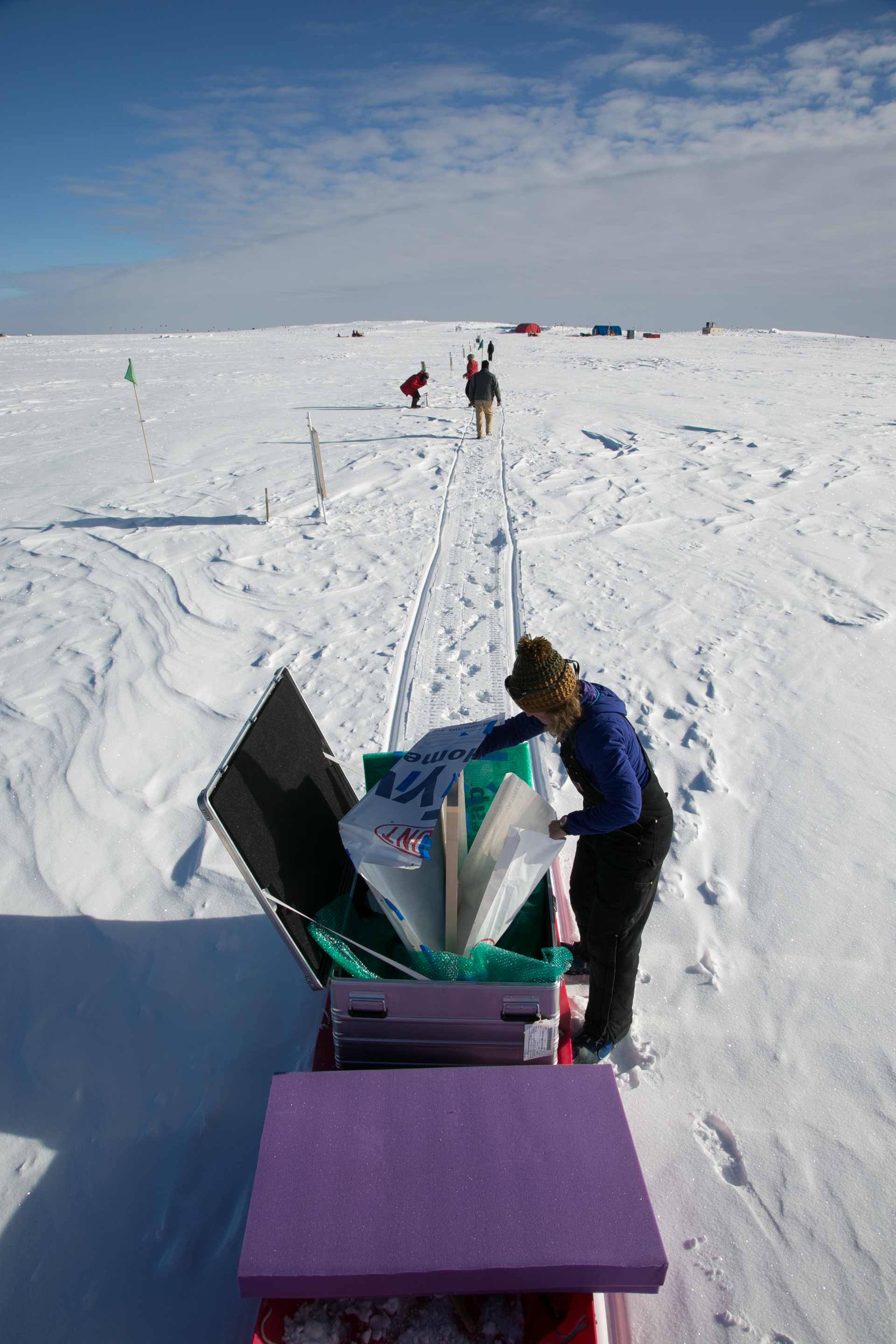

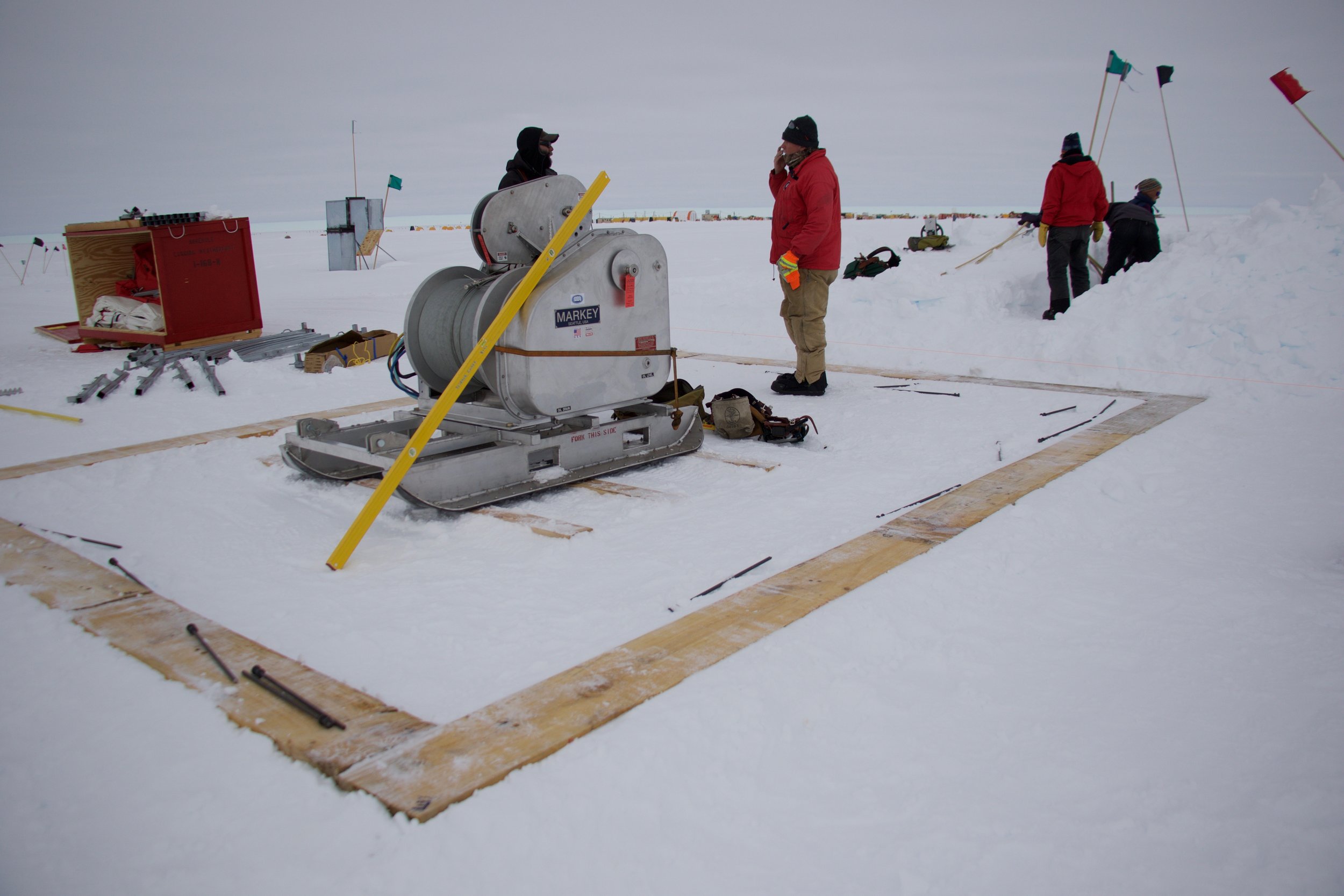

The WAIS Divide site was chosen in around 2003, based on what radar surveys told scientists about the relatively flat bedrock and horizontal layers of ice there. Over the years from 2009-2012, a 3405 meter ice core was extracted from the ice sheet. The borehole was left open, the drilling fluid is about the density of ice, and keeps the walls from collapsing. We will use several types of logging instruments, which we will lower into the borehole using a winch. As we lower and later raise the instruments, they will collect data about the borehole geometry and the stratigraphic layers. When we compare this to the borehole data we collected two years ago, we can see how much the ice sheet has moved at each depth.

The Team

The VeLveT Ice Team consists of myself, Professor Erin Pettit (PI), Professor Rachel Obbard (Co-PI), Professor Sridhar Anandakrishnan (PI on a related project), Anny Sainvil, and Emilie Sinkler. PI stands for Principal Investigator. The PI is the team captain, in effect.

Erin Pettit